Sally Rooney's books hurt me, but I keep going back for more

On literary masochism and finding comfort in sad fiction.

Sally Rooney makes me sad, but I willingly subject myself to the despair.

After three novels and a tragic moment listening to an excerpt on the bus, I knew Intermezzo would ruin me, but I couldn't wait to read it. I couldn't wait to feel.

This preoccupation with sad stories started with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

I must have been six or seven when I read that book, and when the lion died, I remember an intense feeling of loss I hadn’t felt before.

I kept re-reading the passage to feel it again, like I was picking at a scab to feel the sting of relief.

A few years later, when Titanic came out on VHS, my neighbour and I would watch the movie just to see who would cry more.

The game began at the end of the film when Rose is floating on the raft in the water holding Jack's hand. She hears the rescue boat and whispers, "Jack, there's a boat, Jack!”

When Rose realises Jack’s dead, I’d feel the sadness rise up in my stomach, spread into my chest, until the tears would inevitably fall.

"See," I'd think, "I'm feeling!" There was a satisfaction to crying more than my neighbour, and it felt strangely good.

I didn't know it then, but my reaction to the lion dying and Jack freezing to death in the Atlantic ocean were shaping my fascination to literary masochism, and apparently a rehearsal for Sally Rooney Sadness three decades later.

Sally Rooney sadness

I'm certainly not the biggest Rooney fan. I didn't wear a bucket hat while reading Beautiful World, Where Are You or host an Intermezzo release party, although now I kind of wish I had. My fandom has been a slow burn.

One reason for this is that, although I place a high premium on being in tune with the zeitgeist, I never quite manage to read Rooney's books at the peak of their buzz.

The reason I don't read books at the height of their power isn't because of some anti-populist stance, although admittedly, I've been guilty of this before. I want to read the "It" book of the moment so I can join the conversation (I hate that I'm yet to read the much-talked-about All Fours by Miranda July for example).

I'm slightly afraid to admit this, but I believe the universe decides my book schedule. My reading habits are governed by intuition rather than trends.

This time is was different. I was eagerly anticipating Intermezzo’s release after listening to "Opening Theory," an excerpt from Intermezzo in The New Yorker's The Writer's Voice. I felt a despairing longing after listening to the story, which remained heavy on me for months.

As expected, Intermezzo fucked me up. I had to take several crying breaks while reading it (no exaggeration).

The emotions I felt while listening to "Opening Theory" have been shaken up like a shitty snow globe, and I'm sitting here surrounded by remnants of grief. This is what I call…

Sally Rooney Sadness: The grief and longing you feel after reading a Sally Rooney novel.

But why do I find Intermezzo so sad? Scrap that. Why do I find all Rooney novels so sad? And if they're so sad, why do I keep going back for more?

The intense and the intimate

If you describe Rooney novels to a friend, they seem fairly banal: sad people in their twenties and thirties navigating complicated relationships – standard stuff. But these love stories destabilise me, and everyone else it seems.

The relationships in Rooney novels are intense. They make the characters question who they are, and ultimately change them as people.

The intensity of these connections comes to life in the sex scenes. I've often thought back to the line from Conversations with Friends, when just before Frances and Nick have sex, Frances lies there thinking, "I might never be able to speak again after this."

Well, I can’t speak after a reading a Rooney sex scene. They’re brutally hot and feel so real (except for the simultaneous orgasms – who the fuck?). I get flustered every time. Which brings me to Intermezzo. I could cry just thinking about Ivan and Margaret in bed.

In chapter 2 (the chapter excerpted in "Opening Theory"), Ivan meets Margaret at a chess exhibition, and they end up hooking up.

This scene is quite possibly the most excruciatingly beautiful first sexual encounter between two people ever. So much so that when I started Intermezzo, I thought about skipping this chapter to avoid the pain of it all.

Luckily (or not so luckily), I didn't, because the excerpt in The New Yorker was edited way down, and the chapter in the book is longer and more affecting. RIP me.

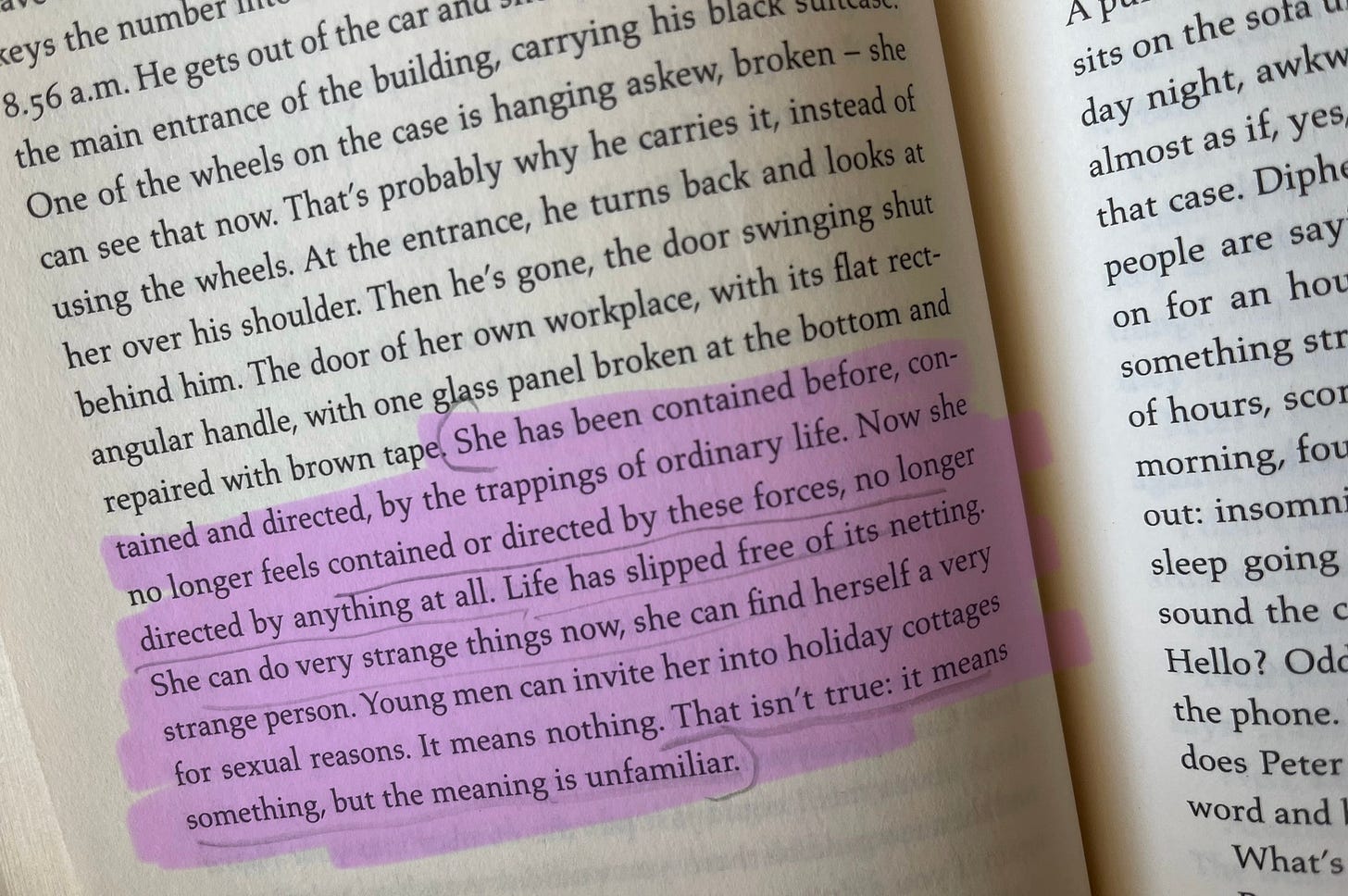

Nothing he has done or felt in this regard before has prepared him remotely for this new experience, with Margaret: the experience of mutual desire. To feel an interpenetration of thought between the two of them, understanding her, looking at her and knowing, yes, even without speaking, what she feels and wants, and knowing that she understands him also, completely.

Rooney captures the first awkward moments of intimacy where you're nervous and self-conscious, fumbling with each other, until the discomfort fades away, and you fall into each other.

The other person seems to know exactly what you want at the precise moment, and you feel completely attuned. It's the kind of sex that makes you cry afterwards (I feel you, Frances!).

Ivan and Margaret's connection reminds me Connell and Marianne’s in Normal People:

You know, I did used to think that I could read your mind at times.

In bed you mean.

Yeah. And afterwards but I dunno maybe that's normal.

It’s not.

It's NOT normal! "Most people go through their whole lives without ever really feeling that close with anyone," Marianne thinks to herself. It's true. This type of connection comes once, twice, maybe three times in your life if you’re lucky

If you’ve experienced this kind of closeness, Intermezzo (and Rooney's other novels) will snatch you out of the present and hurl you back into the beautiful devastation of it all, and you'll be left wailing in the dark like I did in the middle of the afternoon.

The pain of the push-and-pull

It would be boring if characters felt an attraction, got together, and that was that. Luckily, Rooney isn't that kind of author. She explores what characters must grapple with internally and fight against in the other to remain close.

When it comes to things between people (FYI: "Things Between People" by Holly Throsby is a song I used to play when thinking about an intense connection I shared with someone), there are innumerable variables that get in the way of relationships. These variables create a painful push-and-pull.

In Conversations with Friends, Nick and Frances's relationship is fraught from the beginning. Nick is an older, married man, and inherently unavailable, leading Frances to fret and Nick to withdraw – shit for the characters, great for reading.

In Normal People, Connell and Marianne share an oscillating intimacy that leaves you reeling. They orbit each other for years, and every time they reconnect, someone inevitably fucks it up.

These relationships reflect real-life anxious-attachment styles. We all crave closeness, but some of us subconsciously chase relationships with emotionally unavailable people, becoming more anxious when we inevitably can't reach them. Others shut down the moment they get too close because intimacy demands vulnerability, and vulnerability feels unsafe. These dynamics end up in an addictive push-and-pull.

In Intermezzo, the central push-and-pull is between siblings, and it's largely due to misunderstanding.

Peter still thinks of Ivan as the emotionally stunted, awkward incel who only cares about chess. Ivan looks up to Peter but resents the ease in which he lives and his inability to see him as an adult. Their misunderstandings are magnified by grief over their father's death, further alienating them from each other.

Much like Normal People, there's a frustration to these misunderstandings. You think, "You love each other. Stop being stupid!" But you can only see the situation objectively because Rooney grants you access into their inner worlds.

Rooney understands how old wounds turn into coping mechanisms, and that it’s easy to misunderstand when you’re wrapped up in your own story.

As we see in Intermezzo, when Peter and Ivan let their guard down and make an effort to see the world through the other's eyes, they stop pulling away and get close again.

The push-and-pull relationships in Rooney’s novels can remind us of our own tendency to push or pull away, and the relationships lost to this tragic dance.

The inevitably of grief

Grief is not only inevitable, it's a constant. We're grieving all the time. Some grief is macro, more obvious and intense, like the death of a loved one or the end of a relationship. Micro griefs are subtle, often persistent, hidden behind the routines of the day, like the aging process or nostalgia for the past.

Macro grief morphs into micro grief. Micro grief grows into macro grief. Grief is a protean animal with different faces we often don't recognise until later.

Rooney is a master at conveying both macro and micro grief, and her characters are in constant dialogue with it.

In Conversations with Friends, the disappointment of having an unreliable, alcoholic father is a grief that follows Frances everywhere, becoming more painful during interactions with him.

In Normal People, Marianne's brother's abuse and her mother's coldness are a constant source of pain. The absence of real family connection affects how she connects with Connell.

Connell's grief over Rob's suicide is a sudden, devastating loss that triggers deeper anxieties around belonging, and he becomes severely depressed.

The grief in Beautiful World, Where Are You is more existential. Alice mourns the loss of anonymity and questions whether her writing matters. Eileen grieves what she could have achieved if her life had been different.

Grief is a major theme in Intermezzo, but Rooney doesn't handle the father's death in a capital-G Grief way. There's no dramatic last words at his bedside or bawling at the sight of the coffin at the funeral.

Instead, grief shows up in subtle ways, like when Ivan shows Margaret a video of his dog, Alexei. He forgets that his dad is in the video and goes quiet for the rest of the car ride.

In the absence of words, we’re better able to understand Ivan's sadness because we fill the space with our own. That's peak Sally Rooney Sadness right there, the character’s grief becoming a proxy for our own.

The discomfort of uncertainty

Uncertainty is one of my favourite themes in literature, and Rooney explores uncertainty brilliantly.

Whether the instability of late-stage capitalism, the persistence of systemic injustice, the anxiety of climate change, or the widening gap of economic inequality, Rooney shows how uncertainty about the world coincides with uncertainty about the self.

In Beautiful World, Where Are You, Eileen and Alice exchange emails about the collapse of modern civilisation, and what price people are really paying for the convenience of a takeaway sandwich.

In Intermezzo, Peter and Sylvia debate the housing crisis, while Naomi deals with these issues on the ground – she gets evicted and arrested.

Ivan questions whether he wasted his youth playing chess and that his best years are behind him, while Margaret worries about the implications of seeing a younger man.

Uncertainty. Uncertainty. Uncertainty. Life is so fucking uncertain. And, of course, the status of Rooney's relationships are also ambiguous, and this is what makes them so compelling.

In Intermezzo, Peter and Sylvia exist in a liminal space – neither lovers nor friends. They love each other deeply but can't be together, so Peter lives in a painful limbo for six years – nostalgic for the past but unable to begin a future without her.

As readers, we're suspended in this state of unknowing, made even more ambiguous through Rooney’s accurate representation of contemporary communications, e.g. the anxiety of waiting for a text. We keep reading to find out if the characters will get it together, and we'll be given relief.

But life is rarely resolute, and resolution is the stuff of trashy romance novels. An author's ability to sit with discomfort and make space for uncertainty makes for realistic fiction – painful, yes, but real.

Representations of uncertainty in art makes me feel less alone, like maybe all the things I doubt are normal and okay. But there's also a sadness in the realisation that life can never be certain, that like grief, uncertainty is inevitable.

Literature is a knife

I feel sad about Ivan and Margaret, Peter and Sylvia, Peter and Naomi, and of course, Peter and Ivan. It’s like the characters in Intermezzo have become a container for unresolved feelings, their sadness has intermingled with my own.

Earlier this year, I watched an interview with Pola Oloixarac on the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art’s channel. She says she’s interested in literature that hurts, and quotes Mexican writer Margo Glantz:

Literature is like a knife that you have in front of your heart while waiting for someone to push it deeper, very softly, as you say, “More, yes, push it more.”

If literature is what it means to be alive, then good literature should hurt because life hurts. The uncertainty, the grief, the push-and-pull, and intense connections lost – this stuff is painful. But we can become numb to pain. We bury our grief and move on, because that’s what life demands of us – we have to keep going.

David Foster Wallace once said, fiction is one of the few places where loneliness can be both confronted and relieved.

Maybe that’s why I avoid reading Rooney’s novels – because they’re confronting. But in the end, I pick them up, because just like the sadness of watching Jack sink into the Atlantic ocean, I want to hurt. I need to hurt.

Like pressing on a bruise to remember how we injured ourselves, we need literature to reflect our pain back at us. To confront the sadness we have buried, to release it. To admit we feel lonely, and feel less alone through the admission. That’s Sally Rooney Sadness, and why we keep going back for more.

If you want to support my writing, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Or you can buy me a one-off coffee to show your appreciation! A portion of your contribution will go to Common Ground, a First Nations not-for-profit working to shape a society that centres First Nations people by amplifying knowledge, cultures and stories.

Thanks for all these insights into Intermezzo (and the other novels). Especially, I like the points about confusion, and macro and micro grief. I was thinking myself that instead of those "dramatic last words at his bedside or bawling at the sight of the coffin at the funeral" scenes, starting the novel after the funeral gave us a portrait of how life carries on for the bereaved, and we have to continue to deal with grief alongside everything else life throws at us, and how that can be overwhelming, sometimes.

(If you're interested, I also wrote a post on Intermezzo: https://storyenergies.substack.com/p/lovepain-attraction-and-repulsion)

I have never read her and not sure what is stopping me. Should I not go down that rabbit hole? I didnt like the first few episodes of Normal People so I never picked up a book. Felt so maudlin. I love Elena Ferrante though which I think of in the same breath for some reason.